From Taxidermy to Fake Food

Scottish Field Magazine sat down with Kerry, founder of the Fake Food Workshop.

See below a transcript of this interview with journalist, Morag Lindsay, May 2023

'Taxidermy is another form of replication...

...endeavouring to mimic life in its most still form.

Sculpting food allows me to capture that same level of detail and bring a sense of history to life'

Tell us about your background. How did you get into making fake food?

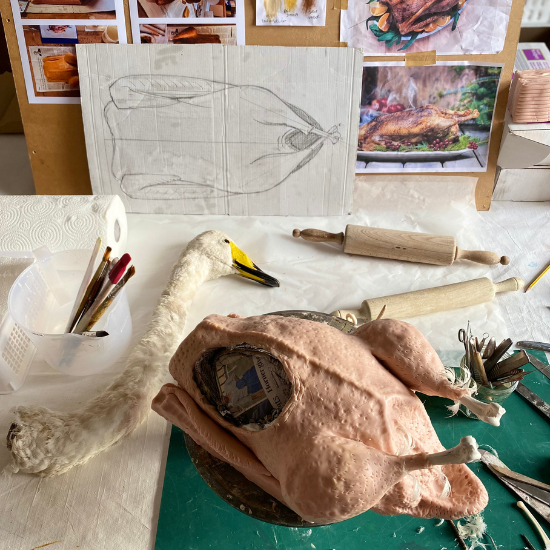

“I grew up in the North Pennines where the hills and local wildlife were my playgrounds, and my father’s woodworking studio was a place to build things and have fun. I studied fine art sculpture in Yorkshire and later earned a Master’s degree in Museum Studies while working for English Heritage. Moving to Scotland, I trained in taxidermy with George Jamieson in Cramond. Taxidermy’s intricate process taught me to understand anatomy and form, which has been invaluable in creating sculpted food, such as a roast-suckling pig or goose for banquet displays.”

How much of your skill is self-taught? What do you love about making fake food?

“A lot of my skills were developed through hands-on practice. My first professional role was as Artist in Residence for the Vindolanda Trust on Hadrian’s Wall, where I carved Roman altar stones and painted frescoes. Taxidermy is another form of replication—endeavouring to mimic life in its most still form. Sculpting food allows me to capture that same level of detail and bring a sense of history to life.”

Who are your usual clients? Tell us about some notable projects.

“Most of our work is for historic properties and events companies, but we also collaborate with the film industry. For example, Warner Bros. contacted us after seeing my sculpted ice cream products. It was exciting to contribute pieces for the Barbie film, especially since my children went to the cinema to see the fake ice creams on screen! Another fun project was creating a gun encapsulated in jelly for Netflix’s The Gentleman premiere. The layered resin process was challenging but rewarding.”

What’s the most complicated piece you’ve worked on?

“Sometimes the simplest items are the hardest to replicate. A cucumber sandwich, for instance, requires the bread to look light and bouncy, the cream cheese to appear smooth and creamy, and the cucumber slices to look fresh. Achieving that balance of textures is always a challenge.”

What materials do you use? Does it vary by project?

“Our go-to material is Jesmonite because of its versatility, but we also use resins and clays. For historical menus, we start with silicone molds of real food and reference recipes, period illustrations, and historical paintings to ensure accuracy.”

What’s been your favorite creation so far?

“Usually, it’s the last piece I’ve made. Recently, I’ve enjoyed creating a large bowl of kedgeree for Hill House, National Trust, and a plate of grilled kippers. Both had their unique challenges, which keeps things exciting. Next week, we’re sending asparagus sculptures to the Museum of Worcester.”

How do you connect food art with history?

“Food isn’t just sustenance; it’s a lens through which we connect with history, culture, and storytelling. Every piece we create is rooted in research, whether it’s studying historical recipes or collaborating with curators. It’s incredibly rewarding to see these creations spark conversations and bring history to life.”

Scottish Field Magazine

Morag Lindsay talks to a sculptor of fake food about her unique career.

Explore Our Creations

We invite you to discover the magic of sculpted food at the Fake Food Workshop.

Whether it’s browsing our Food Hall, exploring New Collections, or commissioning a Custom Order, each piece reflects a commitment to artistry and authenticity.